Execution by Jury Override - Part III: Bobby Marion Francis

This is Part III of Execution by Jury Override, TFDP's series reviewing the cases of those executed in Florida as a result of jury override. This Part discusses the case of Bobby Marion Francis.

Welcome to Part III of Execution by Jury Override, the latest series by TFDP. (Part I can be accessed here. Part II can be accessed here.)

Introduction

Before Hurst,1 Florida allowed what is called a “jury override,” which is where the trial court imposed a sentence of death despite the jury recommending a sentence of life. According to an article published by the Florida State University Law Review in spring 1985 by Michael Mello and Ruthann Robson, Judge over Jury: Florida’s Practice of Imposing Death over Life in Capital Cases,2 as of that time, “Florida [was] one of only three states [that] allow[ed] a judge to override a jury’s recommendation of life imprisonment.” As TFDP previously covered, two people currently on Florida’s death row were sentenced to death by jury override.

As Mello and Robson further explained, as of spring 1985, Florida was “the only state that ha[d] actually executed a person despite the jury’s recommendation of a life sentence.” As of that time, Florida had executed three people sentenced to death by jury override. Consistent with Mello and Robson’s prediction, Florida continued doing so with at least one more execution in 1995. This series reviews the cases of those executed as a result of jury override.

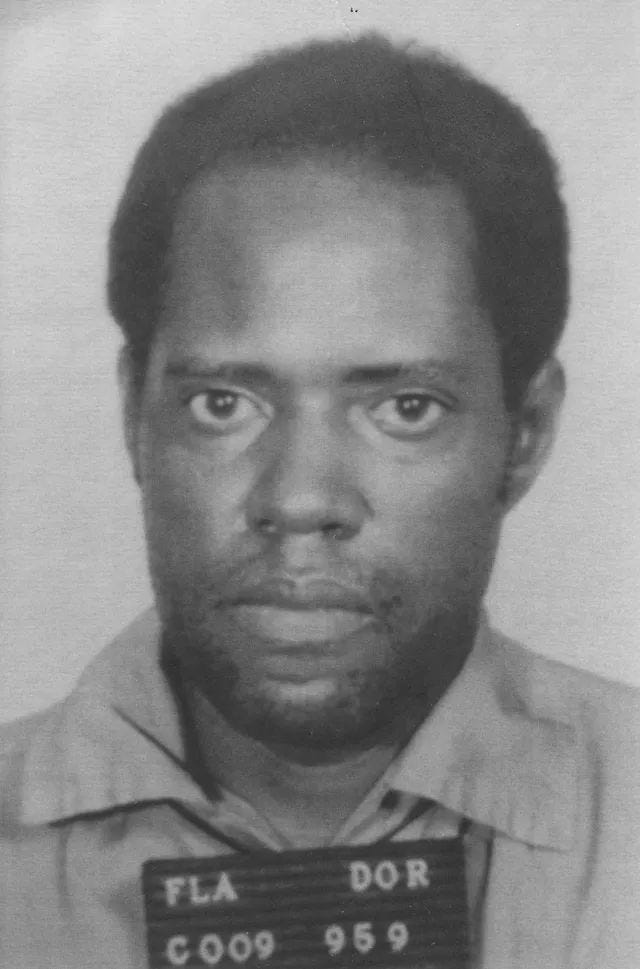

Bobby Marion Francis

Bobby Marion Francis was the third person executed due to a jury override when he was executed by electrocution on the morning of June 25, 1991.

Three Trials

Francis was originally convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to death in late 1976 following a jury’s unanimous recommendation for death.3 On appeal, the Florida Supreme Court “relinquished jurisdiction to the trial court by order entered June 20, 1978,” and the trial court determined Francis’s attorney was ineffective.4 Accordingly, Francis was given a new trial.

Francis was retried in August 1979 and again convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to death following the jury’s unanimous recommendation for death.5 On direct appeal, by decision dated April 15, 1982, the Florida Supreme Court determined Francis “was denied due process of law by the selection of the jury outside his presence,” which ”resulted in prejudicial error.”6 Accordingly, the Court reversed his conviction and remanded for a new trial.

In the third trial, the trial court changed venue from Monroe to Dade County.7 The jury again convicted Francis but recommended a life sentence “after deliberating for less than an hour.”8 Despite the jury’s recommendation, the trial court imposed the death sentence.

As aggravating factors, it found that the murder was committed to hinder lawful exercise of the police powers of the state; that it was especially wicked, evil, atrocious, and cruel; and that it was cold, calculated, and premeditated without any pretense of moral or legal justification. As a mitigating factor, the trial court found that although Francis had been convicted of a felony, this felony conviction was subsequent to the murder, and therefore he had no significant history of prior criminal activity. It also stated that it had considered Francis' recent good behavior in prison. The court found that the mitigating factors and strong recommendations of the jury do not outweigh the significant strong factors in aggravation.9

On direct appeal, the Florida Supreme Court affirmed Francis’s conviction and sentence. In pertinent part, Francis challenged the jury override. The Court disagreed, writing:

On the present record, we find no reasonable basis discernible from the record to support the jury's life recommendation. Perhaps, the jury's recommendation was the result of the highly emotional closing argument of defense counsel made on March 29, 1983, the Tuesday before Easter Sunday, which amounted to a non-legal sermon referencing several times to Easter, the Last Supper of Jesus and his disciples, and the covenant of God's love for humanity which must be passed along with the cup of forgiveness to the next generation of children.

. . . .

Applying the test announced in Tedder, we conclude that the facts in this case suggesting a sentence of death are so clear and convincing that no reasonable person could differ.

Finally, we find no merit to Francis' contention that the trial court unconstitutionally sentenced him to death because he chose to exercise his constitutional right to a jury trial and rejected a plea offer of life imprisonment. There is no record support for Francis' assertion that the trial court, just prior to the return of the jury verdict, promised a sentence of life if Francis would plead guilty. Even were there record support for this assertion, we find no reversible error. The trial court properly found several aggravating factors to be proven beyond a reasonable doubt. The sentence of death in this case represents a reasoned judgment based on the circumstances of the capital felony and the character of the offender after giving due consideration to the jury's recommendation.10

Justice Overton concurred in result with an opinion, noting concerns about the prosecutor but emphasizing that “[g]iven the nature of th[e] killing,” he found “the jury override to be appropriate.”11 Justice Shaw also concurred in result without an opinion.

Justice McDonald concurred in result on conviction and dissented as to the sentence, writing in pertinent part:

On the sentence, I conclude that a life sentence is appropriate because of the jury's recommendation. One has to consider the circumstances of this event, the family connections, the nature of the victim, the treatment of others involved. These are reasonable grounds for a jury to recommend life.12

The U.S. Supreme Court denied certiorari on January 21, 1986, with Justices Brennan and Marshall dissenting.

Prior Warrants

First Warrant

In September 1987, the Governor signed a death warrant scheduling Francis’s execution for November 16.13 Francis filed a motion for postconviction relief raising five claims:

1) he had been penalized for going to trial rather than pleading guilty; 2) his trial counsel had rendered ineffective assistance by not discovering and presenting certain nonstatutory mitigating evidence during the penalty phase; 3) the state engaged in misconduct regarding a witness' (Charlene Duncan) testimony; 4) he had been denied his right to confront another witness (Deborah Wesley); and 5) the state attorney's office had a conflict of interest in prosecuting Francis because a previous state attorney had represented a witness against Francis while that attorney did criminal defense work.14

After an evidentiary hearing on the postconviction motion, the trial court denied relief. Francis appealed, and the Florida Supreme Court granted a stay to review his claims.15

Francis also filed a petition for writ of habeas corpus, which focused solely on the jury override issue.16 On November 2, the Florida Supreme Court issued a decision denying Francis’s claim, finding that the claim was procedurally barred and without merit.17

On June 2, 1988, the Florida Supreme Court issued its decision on Francis’s postconviction appeal affirming the trial court’s denial of relief. Justice Barkett dissented with an opinion in which Justice Kogan joined, writing that she would find Francis’s trial counsel ineffective in failing to present mitigation that prejudiced Francis. Regarding jury overrides, Justice Barkett wrote:

[T]his Court has strictly applied the Tedder standard in its review of jury overrides. We have not hesitated to reverse jury overrides that lay beyond the trial court's discretion because of the presence of valid mitigating evidence upon which the jury recommendation reasonably could have been based. E.g., Fead; Ferry; Amazon. Thus, [counsel’s] failure to present such mitigating evidence at the sentencing hearing results in an unreliable sentence that is not susceptible of correction on appeal. If only a weak case for mitigation is found in the record, this Court has been far more inclined to sustain the override based on the assumption that no other mitigating factors existed.

. . . .

I conclude that this probability exists. Had Francis' counsel presented and argued all the available evidence in mitigation, he might have established several valid mitigating factors in support of the jury's recommendation. The sheer weight of this evidence alone may have been sufficient to compel a different outcome, especially in light of the federal and state law governing mitigating factors. . . .

All of these factors, presented together and argued in the sentencing phase, might have been sufficient to have compelled the trial court to accede to the jury recommendation under Tedder, under the doctrine of proportionality, or under the federal requirement of reliability; or it may have prompted this Court to reverse the jury override on direct appeal for any of the same reasons. Accordingly, I conclude that confidence in the outcome has been undermined within the meaning of Strickland, and I thus would reverse the court below, vacate the sentence of death and order appellant resentenced.18

Second Warrant

On September 12, 1988, the Governor signed Francis’s second death warrant, scheduling his execution for October 4 at 7:00 a.m.

On October 3, Francis filed a federal habeas petition raising eight claims. In a decision dated October 7, the federal district court denied Francis relief. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit “granted a certificate of probable cause and stayed the pending execution.”19

In a decision dated July 24, 1990, the Eleventh Circuit affirmed the district court’s denial of relief. Addressing the jury override issue, the Court wrote:

In Florida, a jury's recommendation of a life sentence is entitled to “great weight,” and may only be overturned by a sentencing judge if “the facts suggesting a sentence of death [are] so clear and convincing that virtually no reasonable person could differ.” Tedder v. State, 322 So.2d 908, 910 (Fla.1975). The jury override procedure in Florida is constitutionally valid only to the extent that it does not lead to arbitrary or discriminatory capital sentencing.

Francis contends that the trial court's override of the jury's recommended sentence of life resulted in an arbitrarily, capriciously, and unreliably imposed sentence of death in violation of the eighth and fourteenth amendments. . . . Taken together, Francis argues, the record before the jury contained mitigating circumstances which provided a reasonable basis for the life recommendation.

The central question is whether the state's application of the override scheme in this case resulted in the arbitrary or discriminatory imposition of the death penalty. Our role is not to second-guess the Florida courts on questions of state law, particularly on whether the trial court complied with the mandates of Tedder, but rather to determine whether the trial court, in Francis's case, imposed the death penalty in an arbitrary or discriminatory manner. Parker, 876 F.2d at 1475.

We find the trial court's override to be neither arbitrary nor discriminatory. First, the Florida Supreme Court noted that the jury's life recommendation may well have been the product of defense counsel's highly impassioned emotional closing argument, and thus under Florida law, the recommendation is not entitled to its normal weight. Francis v. State, 473 So.2d at 676–77. Second, the Florida Supreme Court found the trial court's conclusion that Francis had no significant prior criminal history (which included a 1976 conviction for sale of heroin) to be erroneous. Third, the record demonstrates the existence of three valid aggravating factors; it was a deliberately planned, torture murder, of a government informant. Finally, no valid statutory mitigating factors existed, and the nonstatutory mitigating factors were only (a) that Francis has been a model prisoner and (b) that Francis's co-defendants, whose involvement was insignificant when compared to that of Francis, did not receive the death penalty. Even in override cases, however, the mere presence of mitigating evidence does not automatically provide a reasonable basis for the jury's recommendation. Consequently, we hold that the trial court's override of the jury's life recommendation is not constitutionally infirm.20

The U.S. Supreme Court denied certiorari on April 29, 1991. Justices Marshall and Blackmun dissented, both with opinions.

Final Warrant

In the summer of 1991, the Governor signed a third warrant scheduling Francis’s execution for June 19.21 Francis filed a successive postconviction motion raising four claims:

1) improper jury override; 2) the state knowingly presented misleading evidence concerning the witness elimination/disrupt or hinder governmental function or enforcement of law aggravating factor; 3) finding witness elimination in aggravation violated Ashe v. Swenson, 397 U.S. 436, 90 S.Ct. 1189, 25 L.Ed.2d 469 (1970); and 4) trial counsel rendered ineffective assistance by failing to investigate and prepare for the penalty phase.22

The trial court summarily denied the motion. On appeal, the Florida Supreme Court affirmed in a decision dated June 15. Justice Barkett wrote a specially concurring opinion in which Justice Kogan joined.

The Eleventh Circuit granted a last-minute stay, which the U.S. Supreme Court vacated on June 24.23 Justice Thurgood Marshall dissented.

Execution

Francis was executed on the morning of June 25, 1991. Francis refused a last meal but “did have ice cream and a soft drink” according to a report by the Tampa Bay Times. As to his final words, the Tampa Bay Times reported:

"All I have to say is I have no animosity toward the courts or Mr. Chiles," Francis said in his final statement. Speaking in Arabic, he added, "There is no God but Allah, and Mohammed is his messenger. God is the greatest."

He was pronounced dead at 7:07 a.m. According to a news report, the U.S. Supreme Court denied his final claims just 30 minutes beforehand. Justice Marshall dissented.24 Francis was 46 at the time of his death.

According to a news report, “Gov. Lawton Chiles ha[d] said he does not approve of the 'jury override' law but nevertheless signed Francis's death warrant as a means of forcing a judicial review of the law.”

News Articles

Michael Mello & Ruthann Robson, Judge over Jury: Florida’s Practice of Imposing Death over Life in Capital Cases, 13 Fla. St. U.L. Rev. 31, 34 (1985).

Francis v. State, 529 So. 2d 670, 672 (Fla. 1988).

Francis v. State, 413 So. 2d 1175, 1176 (Fla. 1982).

Francis v. State, 473 So. 2d 672, 674 (Fla. 1985); Francis, 529 So. 2d at 672.

Francis, 413 So. 2d at 1176.

Francis, 473 So. 2d at 674.

Francis, 529 So. 2d at 672; see Francis, 473 So. 2d at 674.

Francis, 473 So. 2d at 674.

Id. at 677-78.

Id. at 678 (Overton, J., concurring in result).

Id. (McDonald, J., concurring in part and dissenting in part).

Francis v. State, 529 So. 2d 670, 671 (Fla. 1988).

Id.

Id.

Francis v. Dugger, 514 So. 2d 1097, 1097 (Fla. 1987).

See generally id.

Francis, 529 So. 2d at 678-79 (Barkett, J., dissenting).

Francis v. Dugger, 908 F.2d 696, 699 (11th Cir. 1990).

Id. at 704 (citations omitted).

Francis v. Barton, 581 So. 2d 583, 583 (Fla. 1991).

Id. at 584.

Singletary v. Francis, 501 U.S. 1227 (1991).

Francis v. Singletary, 501 U.S. 1244, 1244-45 (1991).