Warrant: Background on Duane Owen's Case

Owen has two sentences of death for two separate murders, both of which occurred in the first half of 1984. This post explains the extensive, convoluted background of both cases.

Earlier today, Governor DeSantis signed a death warrant scheduling the execution of Duane Owen for June 15, 2023. (More here.)1

Owen turned 62 in February. He has two sentences of death for two separate murders, both of which occurred in the first half of 1984. There is a convoluted background.

Slattery Murder

The first-in-time crimes underlying Owen’s sentences of death occurred in March 1984. The Florida Supreme Court explained the crimes as follows:

[Karen Slattery] was baby-sitting for a married couple on the evening of March 24, 1984, in Delray Beach. During the evening, she called home several times and spoke with her mother, the last call taking place at approximately 10 p.m. When the couple returned home, just after midnight, the lights and the television were off and the baby-sitter did not meet them at the door as was her practice. The police were summoned and the victim's body was found with multiple stab wounds. There was evidence that the intruder entered by cutting the screen to the bedroom window. He then sexually assaulted the victim. A bloody footprint, presumably left by the murderer, was found at the scene.2

Original Trial

Most of the State’s evidence against Owen at trial “consisted of inculpatory statements made by Owen while he was in police custody and under interrogation.”3

After a trial, Owen was convicted of first-degree murder, along with other crimes, and sentenced to death following the jury’s recommendation for death. The jury’s vote to recommend a sentence of death at the original trial is unclear. The standard at the time was 7-5.

Retrial Granted on Direct Appeal (1990)

On direct appeal, Owen challenged both his conviction and sentence. The Florida Supreme Court reversed Owen’s convictions based the trial court’s admission of evidence that was obtained in violation of Miranda.

Worth mentioning, related to the penalty phase, Owen argued that “the jury should have received a special instruction during the penalty phase stressing the extreme importance of the jury's advisory recommendation. In appellant's view, Florida's standard jury instruction denigrate[d] the role of the jury contrary to” the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Caldwell v. Mississippi, where the Court held that it violates the Eighth Amendment to diminish the jury's sense of responsibility in the guilt phase.4 The Court denied the claim based on prior caselaw.

That decision was issued March 1, 1990.

Certified Question (1997)

Before Owen’s retrial, there was a somewhat unusual occurrence in his case. After the Florida Supreme Court granted a retrial but before the retrial actually occurred, the U.S. Supreme Court held in Davis v. United States “that neither Miranda nor its progeny require police officers to stop interrogation when a suspect in custody, who has made a knowing and voluntary waiver of his or her Miranda rights, thereafter makes an equivocal or ambiguous request for counsel.”5

Based on Davis, the State “moved the trial court to reconsider the admissibility of Owen's confession in light of Davis.”6 The trial court maintained that the confession was inadmissible, and the State filed a petition for a writ of certiorari with the district court of appeal, which ultimately certified the following question to be of great public importance:

DO THE PRINCIPLES ANNOUNCED BY THE UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT IN [DAVIS v. UNITED STATES, 512 U.S. 452, 114 S.Ct. 2350, 129 L.Ed.2d 362 (1994)] APPLY TO THE ADMISSIBILITY OF CONFESSIONS IN FLORIDA, IN LIGHT OF [TRAYLOR v. STATE, 596 So.2d 957 (Fla.1992)]?

Reviewing that question, the Court read Davis to clarify, contrary to its original decision in Owen’s direct appeal, that “federal law did not require [the Court] to rule Owen's confession inadmissible.”7 Further, the Court determined that "Florida's Constitution does not place greater restrictions on law enforcement than those mandated under federal law when a suspect makes an equivocal statement regarding the right to remain silent . . . ."8 In other words, the Court determined that the outcome of its decision on direct appeal would've been different in light of Davis.

As to how the decision applied to Owen’s case, the Court wrote that relying upon its prior decision in Owen’s case “would result in manifest injustice to the people of this state because it would perpetuate a rule which we have now determined to be an undue restriction of legitimate law enforcement activity.”

That being said, the Court wasn’t willing to go so far as to reinstating Owen’s convictions like the State requested. Somewhat similar to what the Court held in Jackson and Okafor after Poole overturned Hurst II and the State tried to reinstate death sentences that had been vacated in light of Hurst,9 the Court determined Owen was still entitled to a new trial because its prior decision vacating Owen’s convictions was final. Of course, Davis still affected the admissibility of the evidence at retrial.

That decision was issued May 8, 1997.

Retrial

Owen’s retrial took place in early 1999. The retrial jury again found Owen guilty of first-degree murder and other crimes. In March 1999, the jury recommended that Owen be sentenced to death by a vote of 10-2, and the judge sentenced Owen to death.

Direct Appeal - Affirmed

On direct appeal from retrial, Owen raised seven claims--related to both guilt and the penalty.10 Again, Owen challenged the admissibility of his confession; that claim was denied.

As to the penalty, Owen again challenged the constitutionality of Florida’s capital sentencing scheme. Interestingly, he made essentially the argument that the U.S. Supreme Court validated in Hurst, which the Court denied:

Further, Owen's specific argument that his death sentence was unconstitutionally imposed because Florida's capital sentencing scheme fails to require that aggravating circumstances be enumerated and charged in the indictment and by further failing to require specific, unanimous jury findings of aggravating circumstances is unquestionably without merit.11

That decision was issued on October 23, 2003.

Chief Justice Anstead and Justice Pariente specially concurred with opinions both noting the issue related to the constitutionality of Florida’s capital sentencing scheme in light of Ring.

The sentence of death for the Slattery crime became final on November 15, 2004, when the U.S. Supreme Court denied Owen’s petition for writ of certiorari.

Postconviction

Owen filed an initial motion for postconviction relief raising eight claims, which was later amended. After an evidentiary hearing, the trial court issued an order denying relief. Owen appealed to the Florida Supreme Court, raising five claims, and filed a petition for writ of habeas corpus, raising three claims. Most of the claims related to claims of ineffective assistance of counsel. Upon review, in a unanimous decision issued May 8, 2008, the Supreme Court of Florida denied relief.12

Hurst Claim

After Hurst, Owen sought relief from his death sentence based on Florida’s unconstitutional capital sentencing scheme (as he had argued several times). Owen’s sentence of death for the Slattery murder became final after June 24, 2002 (the date of Ring v. Arizona) and the jury’s recommendation for death was not unanimous. Under the Court’s original Hurst framework, he would’ve been entitled for relief.

However, his case was still pending after the change in the Court in early 2019. After that, the Court issued an Order directing additional briefing on whether the Court should recede from its prior retroactivity decisions and other issues.

Briefing was completed in June 2019, but the Court’s opinion was not issued until a year later on June 25, 2020—after Poole, which changed the reasoning. As a result, he was denied Hurst relief.13

Worden Murder

Crimes

The information related to the second murder was discovered after Owen was arrested for the Slattery murder, as the Florida Supreme Court explained:

The body of the victim, Georgianna Worden, was discovered by her children on the morning of May 29, 1984, as they prepared for school. An intruder had forcibly entered the Boca Raton home during the night and bludgeoned Worden with a hammer as she slept, and then sexually assaulted her. Owen was arrested the following day on unrelated charges and was interrogated over several weeks. He eventually confessed to committing numerous crimes, including the [Worden] murder and [the Slattery murder].14

Trial

After a trial, the jury convicted Owen of first-degree murder and other crimes and recommended death by a vote of ten to two. The trial judge followed the jury's recommendation and imposed a sentence of death.

Direct Appeal (1992)

On direct appeal, the Florida Supreme Court affirmed Owen’s convictions and sentence of death in a 4-2 decision. Justices Barkett and Kogan dissented and expressed concerns with the admission of Owen’s confession.

That decision was issued on January 23, 1992.

That sentence of death became final on October 13, 1992, when the U.S. Supreme Court denied Owen’s petition for writ of certiorari.

Initial Postconviction (2000)

In his initial motion for postconviction relief, Owen raised several claims related to both guilt and the penalty. On November 5, 1997, the trial court denied Owen's claims. The Supreme Court of Florida affirmed the trial court’s order denial of relief on all claims in a decision issued September 21, 2000.15 Justice Anstead concurred in result only without an opinion.

Successive Postconviction & Habeas (2003)

On June 29, 2001, Owen filed a pro se motion for successive postconviction relief, which the trial court denied. Owen appealed to the Florida Supreme Court and also filed a petition for writ of habeas corpus, in which he raised 11 claims. Seven of those 11 claims were related to “ineffective assistance of appellate counsel.”16 The other claims related to “the constitutionality of Florida's capital punishment statute,” including claims related to the Hurst theory.17

The Florida Supreme Court denied relief on all claims in a decision dated July 11, 2003. Chief Justice Pariente concurred in part and dissented in part with a one-sentence opinion saying: "I concur in the majority opinion in all respects except for the discussion of Ring v. Arizona, 536 U.S. 584, 122 S.Ct. 2428, 153 L.Ed.2d 556 (2002).”

NOTE: Ring was the precursor to Hurst.

Federal Habeas

District Court

On August 7, 2008, Owen filed a petition for writ of habeas corpus in the federal court raising seven claims:

Mr. Owen contends that (i) he was denied his right to remain silent, (ii) he was denied effective assistance of counsel during jury selection, (iii) he was denied effective assistance of counsel during the penalty phase of his trial, (iv) he was denied effective assistance of counsel during the guilt phase of his trial, (v) he was denied an evidentiary hearing during his postconviction proceedings, (vi) he was denied effective assistance of appellate counsel when counsel failed to raise issues regarding the State's impeachment of defense experts on appeal and (vii) he was denied effective assistance of appellate counsel for failing to raise obvious errors made during the penalty phase of his trial.18

In a decision dated November 30, 2010, the Court denied the petition.

Court of Appeals

Owen appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit. In a fairly long opinion dated July 11, 2012, the Eleventh Circuit affirmed the lower court’s decision.

Hurst Claim

After Hurst, Owen sought relief from his death sentence based on Florida’s unconstitutional capital sentencing scheme (as he had argued several times). The Florida Supreme Court affirmed the trial court’s denial of relief based on its retroactivity decision in a decision dated June 26, 2018. Justice Pariente concurred in result with a short opinion, and Justices Lewis and Canady separately concurred in result.

The Death Warrant

Interestingly, the letter from Attorney General Ashley Moody that is attached to the death warrant only references the Worden murder and resulting sentence of death. The Slattery murder and resulting sentence of death is not mentioned. Likewise, the death warrant itself only mentions the Worden murder and does not mention the Slattery murder.

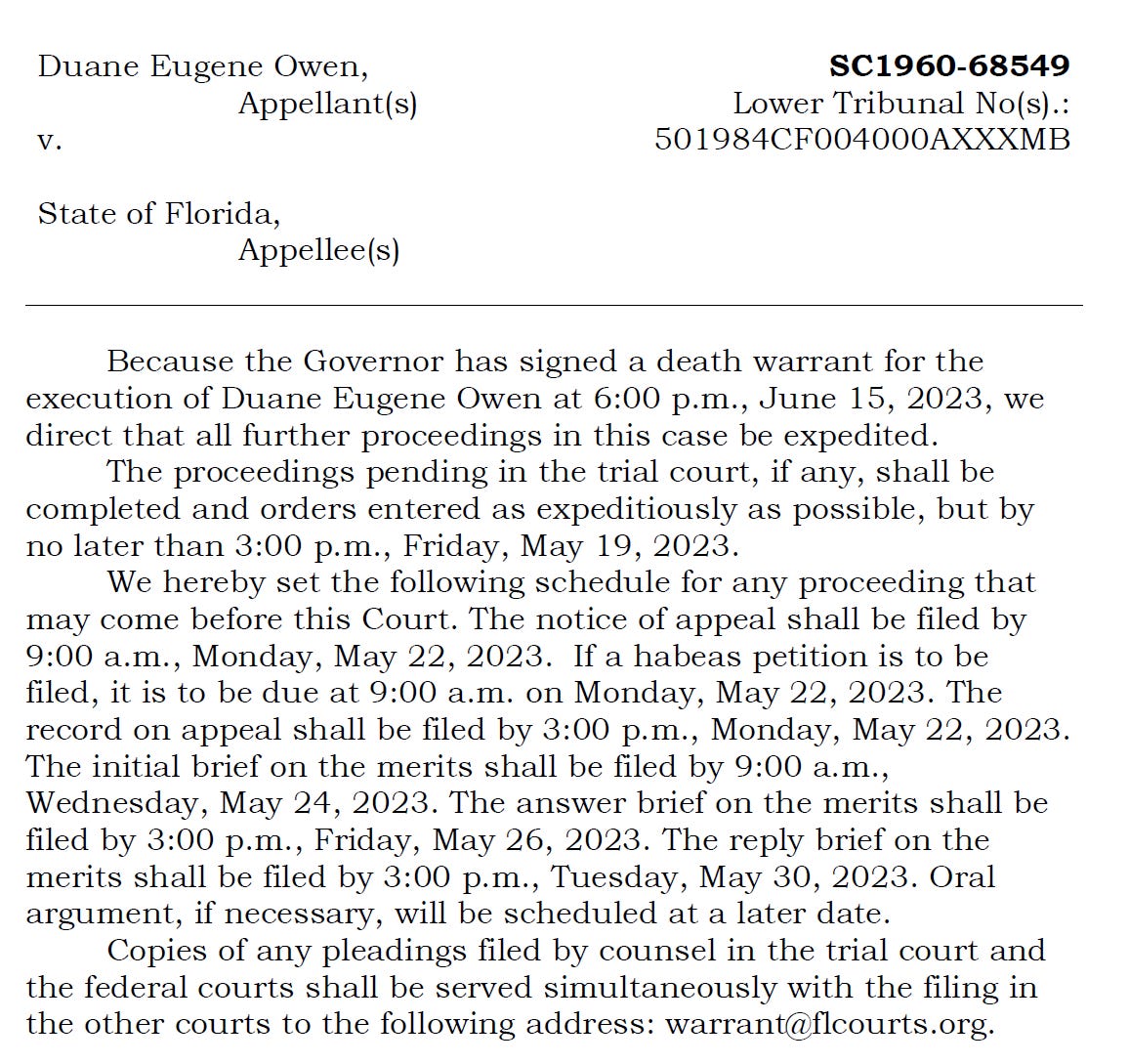

Scheduling Order

This afternoon, the Florida Supreme Court issued a scheduling order for warrant litigation:

My thoughts are with everyone involved in the warrant and execution process.

Apologies for three posts in one day. I originally planned to post this tomorrow, but I am posting this early so that a news outlet can include it in their newsletter tomorrow morning.

Owen v. State, 560 So. 2d 207, 209 (Fla. 1990).

Owen v. State, 696 So. 2d 715 (Fla. 1997).

Owen, 560 So. 2d at 212.

Owen, 696 So. 2d at 717.

Id.

Id. at 719.

Id.

For more on the details of Hurst, which is discussed throughout this post, see the Hurst series available here.

Owen v. State, 862 So. 2d 687 (Fla. 2003).

Id. at 703-04.

Owen v. State, 986 So. 2d 534 (Fla. 2008).

Owen v. State, 304 So. 3d 239 (Fla. 2020).

Owen v. State, 596 So. 2d 985, 986 (Fla. 1992).

Owen v. State, 773 So. 2d 510 (Fla. 2000).

Owen v. State, 854 So. 2d 182, 188 (Fla. 2003).

Id.

Owen v. McNeil, 2010 WL 4942668 (S.D. Fla. Nov. 30, 2010) (footnote omitted).