Execution by Jury Override - Part IV: Bernard "Bo" Bolender

This is Part IV of Execution by Jury Override, TFDP's series reviewing the cases of those executed in Florida as a result of jury override. This Part discusses the case of Bernard "Bo" Bolender.

Welcome to Part IV of Execution by Jury Override, the latest series by TFDP. This is the final part in this four-part series. (Part I can be accessed here. Part II can be accessed here. Part III can be accessed here.)

Introduction

Before Hurst,1 Florida allowed what is called a “jury override,” which is where the trial court imposed a sentence of death despite the jury recommending a sentence of life. According to an article published by the Florida State University Law Review in spring 1985 by Michael Mello and Ruthann Robson, Judge over Jury: Florida’s Practice of Imposing Death over Life in Capital Cases,2 as of that time, “Florida [was] one of only three states [that] allow[ed] a judge to override a jury’s recommendation of life imprisonment.” As TFDP previously covered, two people currently on Florida’s death row were sentenced to death by jury override.

As Mello and Robson further explained, as of spring 1985, Florida was “the only state that ha[d] actually executed a person despite the jury’s recommendation of a life sentence.” As of that time, Florida had executed three people sentenced to death by jury override. Consistent with Mello and Robson’s prediction, Florida continued doing so with at least one more execution in 1995. This series reviews the cases of those executed as a result of jury override.

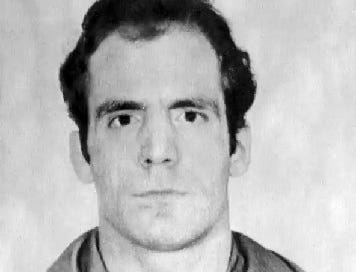

Bernard “Bo” Bolender

Bolender and two codefendants were charged “with four counts of first-degree murder, four counts of kidnapping, and four counts of armed robbery for the brutal torture slayings of four alleged drug dealers.”1 Bolender was tried separately.

Trial and Direct Appeal

On April 25, 1980, the jury convicted Bolender on all charges.2 In the penalty phase, “[n]either the state nor Bolender presented any evidence . . . .”3 After arguments by counsel, the jury recommended that Bolender be sentenced to life in prison. Despite the jury’s recommendation, the judge “imposed the death sentence upon finding all but one of the statutory aggravating factors to apply. The court found nothing in mitigation.”4

NOTE: The judge who sentenced Bolender to death was the same judge who sentenced Beauford White to death by jury override. (He was also the same judge who sentenced John Errol Ferguson to death.)

On direct appeal, among other claims, Bolender challenged the jury override. The Florida Supreme Court denied relief, writing:

There was sufficient collaborating testimony regarding Bolender's participation in these crimes. Based on the evidence and testimony at trial, we agree with the trial court that virtually no reasonable person could differ on the sentence.

Although the Court went on to determine that the trial court erred in applying two aggravating circumstances, it still affirmed White’s sentences due to the absence of any mitigation. His sentences of death became final on May 16, 1983, when the U.S. Supreme Court denied certiorari.

First Warrant

In January 1984, the Governor signed a warrant scheduling Bolender’s execution. Bolender filed a motion for postconviction relief and requested a stay of execution.5 In the motion, Bolender claimed that his “trial counsel rendered ineffective assistance by failing to subpoena a witness properly and by failing to present evidence to mitigate Bolender's sentences.”6 The circuit court stayed the execution to have an evidentiary hearing on Bolender’s claims “and denied the state's request to transfer the case to Bolender's original trial judge.”7

After a hearing in December 1985, the circuit court “orally granted the motion, and vacated Bolender's death sentences.”8 In January 1986, the circuit court “entered a written order, stating his intention to resentence Bolender to life imprisonment if his order is affirmed on . . . appeal.”9 The State appealed to the Florida Supreme Court.

On appeal, the Florida Supreme Court reversed the circuit court’s ruling, determining that the court applied the wrong standard for analyzing a claim of ineffective assistance of counsel:

Bolender's current counsel identified specific omissions, i.e., the failure to have the mother and sister testify. The rest of the test for effectiveness, however, has not been met. Trial counsel testified that he made a strategic choice. Taking into account all the circumstances—the unlikelihood of this testimony impressing the trial judge, the state's ability to undermine these witnesses' testimony through cross-examination and rebuttal, and the disparate treatment afforded the co-perpetrators—trial counsel made a reasonable choice well within the wide range of professionally competent assistance. Strategic decisions do not constitute ineffective assistance if alternative courses of action have been considered and rejected. We hold that Bolender's rule 3.850 motion presented no legitimate claim for postconviction relief and that Judge Klein erred in declaring trial counsel ineffective and in vacating Bolender's death sentences.10

Accordingly, on January 29, 1987, the Florida Supreme Court directed the circuit court to reinstate Bolender’s death sentences. “On September 4, 1987, the trial court enforced the Florida Supreme Court's mandate and reinstated the death penalty. Bolender appealed the reinstatement of the death sentences but such appeal was dismissed.”11

Second Warrant

In 1990, the Governor signed Bolender’s second warrant. Bolender filed another motion for postconviction relief. The circuit court denied Bolender’s claims, and Bolender appealed. On appeal, he raised 11 claims.12 He also filed a petition for writ of habeas corpus, raising several claims. The day before the warrant expired, the Florida Supreme Court stayed Bolender’s execution and set oral argument.13

On May 17, 1990, the Florida Supreme Court issued a decision denying relief and addressing only one of Bolender’s claims—”that the trial court refused to consider, and that trial counsel felt constrained in developing and presenting, nonstatutory mitigating evidence, thereby violating Hitchcock v. Dugger, 481 U.S. 393, 107 S.Ct. 1821, 95 L.Ed.2d 347 (1987).”14

The Court also denied Bolender’s habeas claims. In its decision, the Court dissolved the stay of execution.

Third Warrant

Juts after the Florida Supreme Court denied rehearing on Bolender’s last case, The Governor signed a third death warrant scheduling Bolender’s execution for October 4, 1990.15 Bolender filed a petition for writ of habeas corpus in federal court, raising 17 claims. On October 1, the federal district court granted a stay of execution. In a decision dated February 15, 1991, without an evidentiary hearing, the federal district court denied Bolender’s claims and dissolved the stay.16

Bolender appealed on five claims and challenged the district court's disposition “refusal to conduct an evidentiary hearing on the merits of his contentions.”17 The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit granted a certificate of probably cause to appeal. In an opinion dated March 11, 1994, the Eleventh Circuit affirmed the district court’s denial of relief. The U.S. Supreme Court denied certiorari on November 28, 1994.

Final Warrant

On May 24, 1995, the Governor signed Bolender's fourth death warrant scheduling his execution for July 12, 1995, at 7:00 a.m.18

State Court

Bolender filed another motion for postconviction relief, which the circuit court denied after holding a hearing on July 8.19 On appeal to the Florida Supreme Court, Bolender raised 10 issues:

(1) had the State not misrepresented to the court that codefendant Joe Macker passed a polygraph examination, Bolender would not have been convicted and sentenced to death; (2) newly discovered evidence demonstrates that the State knew of but suppressed evidence of codefendant Macker's allegedly sordid criminal history; (3) newly discovered evidence reveals that the State knew of but suppressed evidence of Mrs. Dianne Macker's illegal activities and questionable credibility; (4) newly discovered evidence reveals that Macker's plea bargain condition that he procure the cooperation of various witnesses for the State violates due process; (5) newly discovered evidence reveals that Macker confessed to and framed Bolender for the murders; (6) newly discovered evidence reveals that the State failed to disclose that Macker was an informant and that the State set up the drug deal which led to the January 8, 1980 murders at Macker's house; (7) an evidentiary hearing is necessary in this case; (8) ineffective assistance of trial counsel; (9) the State interfered with the defense's ability to obtain exculpatory testimony in violation of Brady; and (10) the trial judge was predisposed to impose the death sentence.20

The Court denied relief on all claims. On issue 10 related to the jury override, the Court wrote:

Claim 10 is also procedurally barred. The issue of the judge's override of the jury's recommendation has been thoroughly reviewed and decided in our decisions and the decisions of the federal courts. In his current 3.850 motion and his brief to this Court, Bolender does not point to any matter which was not encompassed within that consideration.21

Justices Shaw, Kogan, and Anstead concurred in result only. The Court temporarily stayed the execution until 7:00 a.m. on July 14, 1995, to allow Bolender to seek relief in federal court.

Federal Court

“[O]n July 11, 1995, immediately before the Florida Supreme Court's decision,” Bolender filed a petition for writ of habeas corpus in federal court.22 The federal district court stayed the execution for five days to “fully consider the claims raised in the petition.”23 The execution was rescheduled for Tuesday, July 18, at 7:00 a.m. The court scheduled oral argument for July 17 at 10:00 a.m. After hearing arguments, on July 17, the court issued a decision denying Bolender’s petition dissolving the stay of execution as of July 17 at 3:00 p.m.

Later the same day, the Eleventh Circuit issued a short decision denying a certificate of appealability, determining that “[t]he district court properly concluded that all of the claims presented in Bolender's petition are procedurally barred under Florida law.”24 The Eleventh Circuit directed the mandate to issue at 5:00 p.m. that day and stayed the execution until 10:00 on July 18, writing:

Because we anticipate that the petitioner will apply to the Supreme Court for a writ of certiorari, we stay petitioner's execution until 10:00 a.m. tomorrow, July 18, 1995, to give the Court an opportunity to consider petitioner's application. Any stay beyond that shall issue from the Supreme Court.25

On the morning of his execution, the U.S. Supreme Court denied Bolender’s final petition for writ of certiorari.

Execution

Bolender was executed on the morning of July 18 by electrocution. He was 42.

According to a news report, his final meal was “baby back ribs, a 16-ounce Delmonico steak and four peaches.” He gave a last statement, reading from a two-page handwritten statement he had prepared.

He was pronounced dead at 10:19 a.m.

News Articles

Bolender v. State, 422 So. 2d 833, 834 (Fla. 1982).

Bolender v. Dugger, 757 F. Supp. 1400, 1402 (S.D. Fla. 1991).

Bolender, 422 So. 2d at 835.

Id. (footnote omitted).

State v. Bolender, 503 So. 2d 1247, 1248 (Fla. 1987).

Id. (footnote omitted).

Id.

Id.

Id.

Id. at 1249-50.

Bolender, 757 F. Supp. at 1405.

Bolender v. Dugger, 564 So. 2d 1057, 1057 (Fla. 1990).

Id.

Id.

Bolender, 757 F. Supp. at 1406.

Id. at 1411.

Bolender v. Singletary, 16 F.3d 1547, 1552 (11th Cir. 1994).

Bolender v. State, 658 So. 2d 825, 84 (Fla. 1995).

See Bolender v. Singletary, 898 F. Supp. 876, 878 (S.D. Fla. 1995).

Bolender, 658 So. 2d at 85.

Id.

Bolender, 898 F. Supp. at 877.

Id. at 878.

Bolender v. Singletary, 60 F.3d 727, 729 (11th Cir. 1995).

Id. at 728.