NEW WARRANT: Kayle Bates' execution scheduled August 19

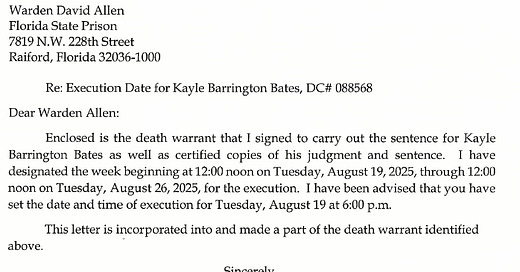

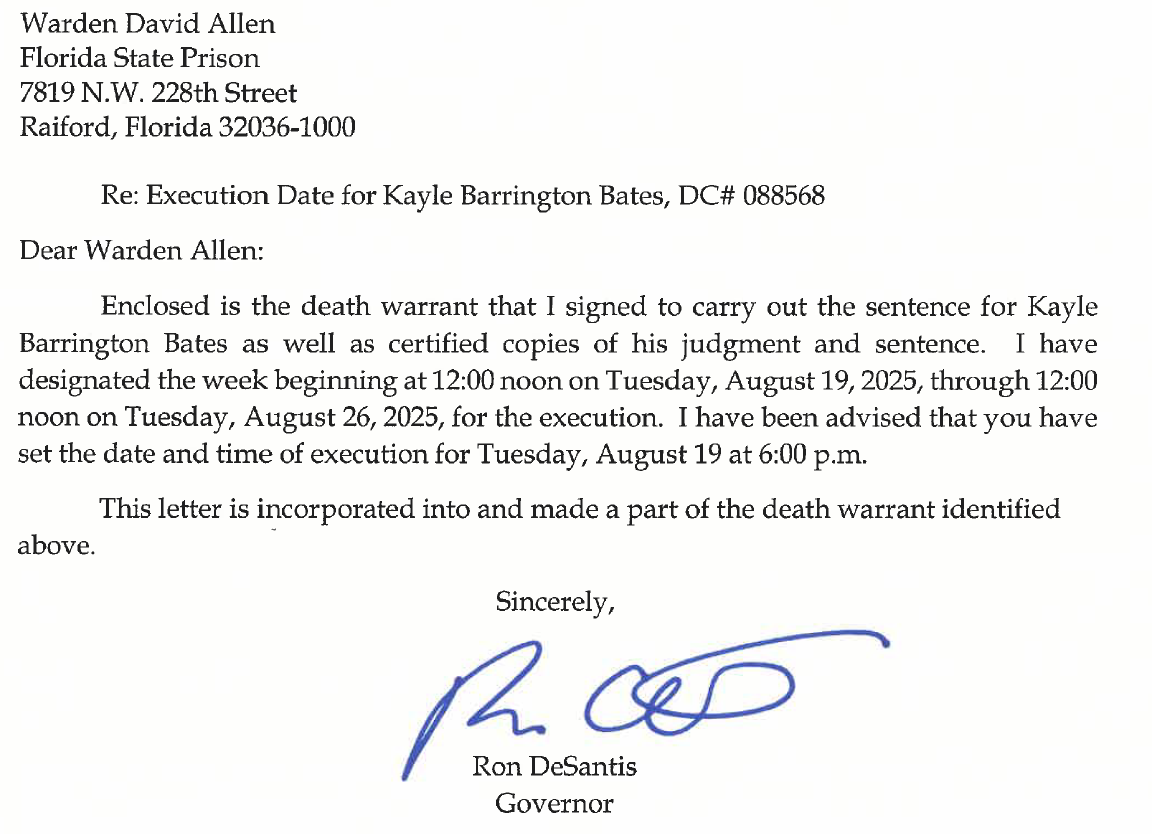

Friday afternoon, Gov. DeSantis signed a death warrant scheduling Kayle Bates’ execution for August 19 at 6:00 p.m. This is the 10th death warrant in the State this year.

Friday afternoon, Gov. DeSantis signed a death warrant scheduling Kayle Bates’ execution for August 19 at 6:00 p.m. This is the 10th death warrant in the State this year.

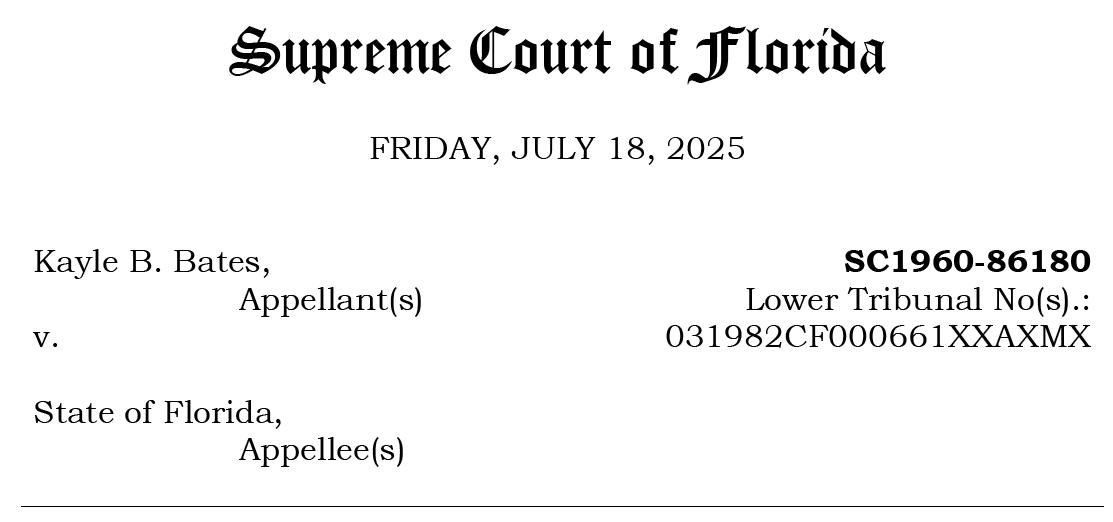

Florida Supreme Court Scheduling Order

Shortly after the Governor issued the warrant, the Florida Supreme Court issued its standard scheduling order for warrant-related litigation.

The order sets forth the following schedule:

July 30 at 11:00 a.m.: deadline to complete circuit court litigation

July 30 at 1:00 p.m.: notice of appeal due

August 1 at 5:00 p.m.: initial brief due

August 4 at 2:00 p.m.: answer brief due

August 5 at 2:00 p.m.: reply brief due

The full scheduling order and warrant can be found on the Court’s docket here.

Background of Bates’ Case

In 1983, a Bay County jury convicted Bates of “the kidnapping, attempted sexual battery, armed robbery, and first-degree murder of Janet White.” The litigation since then has been extensive.1

Trial and Direct Appeal

According to the federal district court, the facts of the underlying crime are as follows:

On the afternoon of June 14, 1982, Janet White, a State Farm Insurance clerk, returned from lunch around 1:00 p.m., as was her normal practice. As she came into the office, she answered the phone. Unknown to her, she was not alone. She knew that Kayle Barrington Bates had stopped by the office earlier that day, talked with her, and left. She did not know that, having seen that she was alone in the office, Bates had returned to the area and parked his truck in the woods some distance behind the building where it could not be seen and waited. She did not know that while she was out at lunch he had broken into the office and was there waiting for her to return. When Bates surprised White she let out a “bone-chilling scream” and fought for her life. He overpowered her and forcibly took her from the office building to the woods where he savagely beat, strangled, and attempted to rape her, leaving approximately 30 contusions, abrasions, and lacerations on various parts of her face and body.2

Further, the Florida Supreme Court explained:

Bates was found at the scene of the crime with the victim's blood on his clothing. Police found other physical evidence connecting Bates to the victim's corpse, including clothing fibers consistent with Bates's pants, Bates's knife case and hat, a watch pin consistent with his watch, and semen on the victim and on Bates's underwear. Bates gave inconsistent confessions that further implicated him in the murder. After he was convicted, the jury recommended the death penalty.3

In sentencing Bates to death, the trial court found that the following aggravating circumstances were established:

1) committed during the commission of three felonies; 2) committed for the purpose of avoiding or preventing arrest; 3) committed for pecuniary gain; 4) especially heinous, atrocious, and cruel; and 5) committed in a cold, calculated, and premeditated manner.4

In mitigation the court found that Bates had no significant history of prior criminal activity.

On direct appeal in 1985, the Florida Supreme Court determined the trial court erred in finding two of the aggravating factors. As a result, the Court affirmed Bates’ convictions but reversed and remanded his death sentence. Several Justices did not agree with this outcome.

Resentencing

At resentencing, the trial court again sentenced Bates to death after allowing him to “present additional evidence in mitigation . . . through the testimony of several witnesses.”5 The Court found “that the aggravating factors (committed during course of kidnapping, attempted sexual battery, and robbery; committed for pecuniary gain; and especially heinous, atrocious, or cruel) outweighed the sole mitigating factor (no significant history of prior criminal activity).”

On direct appeal from resentencing in 1987, the Florida Supreme Court affirmed Bates’ death sentence. Justice Kogan concurred in result. Chief Justice McDonald dissented, joined by Justices Overton and Barkett. His sentence of death became final in October 1987.

1989 Death Warrant

In 1989, a death warrant was signed for Bates’ execution. After the warrant, Bates filed a motion for postconviction relief.

Among other claims for collateral relief, Bates asserted a claim under the First Amendment's Establishment Clause, contending that his convictions and capital sentence were improperly obtained because the trial began with a prayer from the victim's minister. He also raised a related Sixth Amendment claim of ineffective assistance of counsel based on his trial attorney's failure to object to the Reverend's opening invocation. The trial judge recused himself from ruling on the Rule 3.850 motion and was replaced by a different judge.6

The substitute judge stayed Bates’ execution and held an evidentiary hearing on Bates’ claim that trial counsel rendered ineffective assistance at the original sentencing proceeding.

At an evidentiary hearing on that motion, Bates' trial counsel testified that he thought “nothing of the prayer” because it neither encouraged the jury to convict nor acquit Bates. However, in a self-described act of “pure speculation,” counsel opined that the prayer could have prejudiced Bates given the “racial tension” involved in the case. (Bates is black and his victim was white.)7

After the hearing, the judge held that counsel had, indeed, been ineffective and ordered that Bates have a new sentencing hearing before a jury. The trial court summarily denied the other claims as either “abandoned or . . . procedurally barred.”8 Bates appealed.

On appeal, the Court “affirmed [the trial court’s] decision in all respects, including the denial of Bates' dual challenges arising from the prayer. The court rejected Bates' substantive Establishment Clause challenge as procedurally barred because it was not properly raised at trial, and it summarily rejected ‘[a]ny allegations of ineffectiveness raised incidentally’ to that substantive claim as being ‘without merit.’”9

Second Resentencing

At his second resentencing in 1995, the jury recommended death by a vote of 9-3. The trial court followed the jury’s recommendation and sentenced Bates to death again.

The court found three aggravating circumstances: capital murder committed during an enumerated felony (kidnapping and attempted sexual battery); capital murder committed for pecuniary gain; and HAC. The court found two statutory mitigating circumstances: no significant history of prior criminal history (significant weight); and appellant's age of twenty-four at the time he committed the murder (little weight). The court found eight nonstatutory mitigating circumstances: appellant was under some emotional distress at the time of the murder (significant weight); appellant's ability to conform his conduct to the requirements of the law was impaired to some degree (significant weight); appellant's family background (some weight); appellant's national guard service (little weight); appellant was a dedicated soldier and patriot (little weight); appellant's low-average IQ (little weight); appellant's love for his wife and children and being a supportive father (some weight); and appellant was a good employee (little weight).

On direct appeal in 1999, the Florida Supreme Court affirmed Bates’ death sentence. His sentence became final in October 2000.

Postconviction

Bates filed a postconviction motion “raising eighteen claims with several subclaims.”10 He also filed a motion for postconviction DNA testing.

The postconviction court “granted an evidentiary hearing on two of the claims, and summarily denied the remaining claims.” The court also denied his motion for DNA testing and denied his “remaining two claims after conducting an evidentiary hearing.”

Bates appealed “the denial of four . . . claims, containing numerous subclaims, and . . . also filed a petition for a writ of habeas corpus,” raising two claims. The first claim was a “refashion[ed]” claim of ineffective assistance of counsel. In the second claim, Bates argued that 12 photographs were improperly admitted at trial. On appeal in 2005, the Florida Supreme Court affirmed the denial of Bates’ postconviction claims and also denied his petition for writ of habeas corpus.

On the DNA issue, he argued “that he did not commit the murder and that DNA testing of hairs, blood, semen, and other evidence would prove his innocence.” The Court found “that it was reasonable for the postconviction court to conclude that the results of the testing that Bates seeks in his motion would not produce ‘a reasonable probability’ of Bates' exoneration.” The Court further explained:

We recognize that the prosecutor argued at trial that Bates raped the victim, and we also recognize that the DNA testing could show that Bates' semen was not found in the victim's vagina. However, the jury did not find Bates guilty of sexual assault but, rather, found Bates guilty of attempted sexual assault. Again, in view of the defendant's statements as to what he did during the brief time period in which the victim's murder occurred, which statements were consistent with attempted sexual battery, and also in view of the physical evidence in the record, we agree with the trial court that the DNA of the semen in the victim's vagina “was not a critical link in the proof against the defendant at trial.” DNA Order at 5.

Senior Justice Anstead concurred in part and dissented in part, writing: “I cannot agree with the majority that Bates is not entitled to have DNA testing of certain evidence in order to bring more certainty to the sentencing process.”

Federal Habeas

In March 2009, Bates filed his federal petition for writ of habeas corpus, asserting several claims including “(1) that his trial counsel rendered ineffective assistance in failing to object to the prayer in the presence of the jury venire before voir dire, particularly once the victim's husband gave testimony implying that she had been a member of that minister's congregation; and (2) that his due process rights under Simmons were violated when, at his 1995 resentencing, the trial court refused to instruct the jury about his parole ineligibility.”11 In an order issued on September 28, 2012, the district court denied the 28 U.S.C. § 2254 petition, finding that his ineffective assistance claim was procedurally barred and that the Florida Supreme Court's rejection of his parole ineligibility claim was entitled to deference under the standards prescribed by the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 (AEDPA).

On September 28, 2012, “the district court denied the 28 U.S.C. § 2254 petition, finding that his ineffective assistance claim was procedurally barred and that the Florida Supreme Court's rejection of his parole ineligibility claim was entitled to deference under the standards prescribed by the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 (AEDPA).”

Bates filed a motion to alter or amend the district court's judgment under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 59(e), contending that the court had erroneously found that his ineffective assistance claim was procedurally defaulted. The court granted the Rule 59(e) motion, concluding that the Florida Supreme Court had indeed reached the merits of that claim, but determined that federal habeas relief was still not warranted because the state court's merits determination was entitled to AEDPA deference.

The U.S. Court of Appeals granted a Certificate of Appealability on two issues:

(1) whether trial counsel rendered ineffective assistance in failing to object to the prayer; and (2) whether “the trial court's refusal to instruct the jury about [Bates'] parole eligibility, including the effect of consecutive sentences he had left to serve, was contrary to law established by the United States Supreme Court or objectively unreasonable in light of such precedent.”12

On appeal in September 2014, the Eleven the Circuit affirmed the denial of Bates’ habeas petition.

Hurst Claim

After Hurst,13 Bates filed a successive motion for postconviction relief. In January 2018, the Florida Supreme Court denied Bates’ claim because his sentence of death became final before Ring v. Arizona in 2002.14 Justice Pariente concurred in result.

Motion to Interview Jurors

Bates filed a motion to interview a juror who served at his 1983 trial. “Bates claim[ed] to have learned at some unspecified time (but years after his conviction) that the juror is the second cousin of a person who was married to the victim's sister.”15 The circuit court denied the motion. On October 24, 2024, the Florida Supreme Court affirmed the denial. Bates’ petition for writ of certiorari was just denied on June 30.

My thoughts are with everyone involved in the warrant- and execution-related process.

My apologies for my delay on getting this post up. I always try to get it out the same day as the warrant, btu I have been traveling for a project on a capital pro bono case this weekend.

Bates v. Sec’y, Fla. Dep’t of Corrs., 768 F.3d 1278 (11th Cir. 2014).

Bates v. State, 398 So. 3d 406, 406-07 (Fla. 2024)

Bates v. State, 465 So. 2d 490 (Fla. 1985).

Bates v. State, 506 So. 2d 1033 (Fla. 1987).

Bates, 768 F.3d at 1285.

Id.

Bates v. Dugger, 604 So. 2d 457, 458 (Fla. 1992).

Bates, 768 F.3d at 1287.

Bates v. State, 3 So. 3d 1091, 1097 (Fla. 2009).

Id.

Id.

Bates v. State, 238 So. 3d 98 (Fla. 2018).

Bates, 398 So. 3d at 406.

Praying for family of the victim.