Volusia County: Jury recommends death for James Guzman

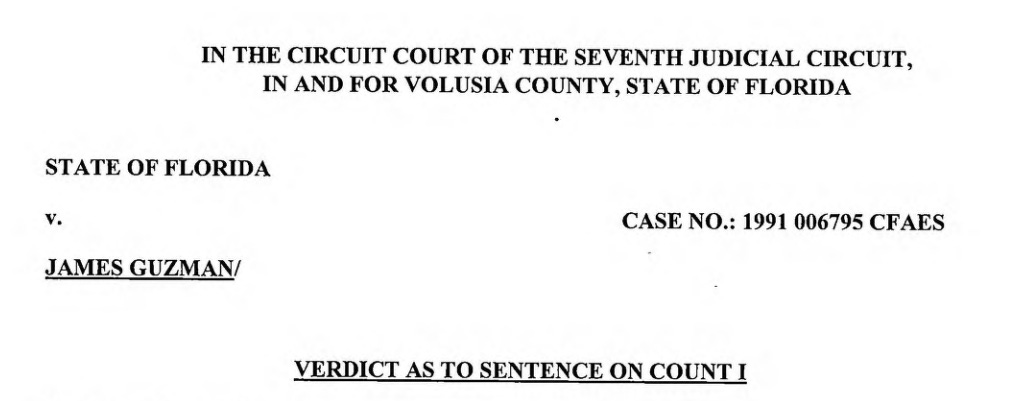

Last week, a Volusia County jury unanimously recommended that James Guzman be resentenced to death.

Last week, a Volusia County jury unanimously recommended that James Guzman be resentenced to death. This was Guzman’s new penalty phase, granted after Hurst.

Background

Trials

In December 1991, James Guzman was arrested on first-degree murder charges. After his original trial, he was convicted and sentenced to death. On direct appeal, in a decision dated September 22, 1994, the Florida Supreme Court reversed Guzman’s convictions and sentence of death and granted him a new trial due to his public defender’s conflict of interest.1

Guzman’s second trial began on December 2, 1996—five years after his arrest. This time, he waived his right to a jury trial in both the guilt and penalty phases.2 Again, Guzman was convicted and sentenced to death. On direct appeal, the Florida Supreme Court affirmed Guzman’s convictions and death sentence.

Postconviction

In 2000, Guzman filed a motion for postconviction relief. While that motion was pending, he also filed a motion seeking DNA testing of evidence found at the crime scene. The circuit court denied his motion for postconviction relief, and Guzman appealed, presenting the following claims:

(1) the State committed a Giglio violation by permitting false testimony at trial denying that State witness Martha Cronin was paid for her testimony against Guzman; (2) the State committed a Brady violation by failing to disclose to the defense the State's $500 payment to Cronin; (3) the State destroyed potentially exculpatory DNA evidence—a clump of hair from the crime scene—in bad faith; and (4) Guzman was denied a fair trial due to the prosecutor's presenting misleading evidence and improper argument.3

Guzman also filed a petition for writ of habeas corpus, raising two claims: “(1) his waiver of a jury for the penalty phase of his trial was invalid in light of Ring and Apprendi; (2) he may be incompetent to be executed.”4 In a decision dated November 20, 2003, the Florida Supreme Court denied Guzman relief on all counts but remanded to the trial court for a ruling on the Giglio claim.

On remand, the same judge who presided over Guzman’s retrial and initial postconviction again denied Guzman’s Giglio claim. Guzman appealed to the Florida Supreme Court. On appeal, in a decision dated June 29, 2006, the Florida Supreme Court affirmed the trial court’s denial of relief.5 Justice Anstead dissented, writing:

Because I conclude that the majority's analysis and holding on the Giglio v. United States, 405 U.S. 150, 92 S.Ct. 763, 31 L.Ed.2d 104 (1972), claim is contrary to controlling precedent of this Court and the United States Supreme Court, I am compelled to dissent. Contrary to this controlling precedent, the majority opinion sends out an alarming signal as to this Court's concern with the presentation of perjured testimony in criminal trials generally, and in death penalty cases in particular.6

Federal Habeas

Following the denial of state court postconviction relief, Guzman sought relief in federal court. In a decision dated March 17, 2010, the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Florida determined Guzman was entitled to relief on his Giglio claim, writing:

[T]he Court concludes that the false testimony was material, and there was a reasonable likelihood that the false testimony could have affected the trial court's judgment as the fact-finder in this case. Thus, Petitioner has shown that the false testimony was not harmless beyond a reasonable doubt and that it had a substantial and injurious effect or influence in determining the trial court's verdict.

The Supreme Court of Florida correctly identified Giglio as providing the standard for the adjudication of this issue; it further concluded that the false testimony was not material because of the substantial impeachment evidence against Ms. Cronin and because Ms. Cronin's testimony regarding Petitioner's guilt was independently corroborated and supported by other record evidence. Under the facts of this case and the applicable federal law, Petitioner has shown that the decision of the Supreme Court of Florida was contrary to, or involved an unreasonable application of, clearly established Federal law, as determined by the Supreme Court of the United States. Likewise, Petitioner has shown that the decision of the Supreme Court of Florida was based on an unreasonable determination of the facts in light of the evidence presented. For this reason, this issue is meritorious, and Petitioner is entitled to habeas relief on this claim.7

The Court also found that Guzman was entitled to relief on his Brady claim, writing:

[A]lthough the Supreme Court of Florida also relied on its finding that Ms. Cronin's testimony regarding Petitioner's guilt was independently corroborated and supported by other evidence, the Court discussed above that such evidence was not overwhelming and was insufficient to render the false testimony of Ms. Cronin and the lead detective immaterial.

As such, the false testimony and the withholding of the evidence pertaining to the reward was material, and there was a reasonable probability that the false testimony and the evidence would have affected the trial court's judgment as the fact-finder in this case. Petitioner has demonstrated that the false testimony and the withholding of the evidence was not harmless beyond a reasonable doubt and that it had a substantial and injurious effect or influence in determining the trial court's verdict.

The Supreme Court of Florida correctly identified Brady as providing the standard for the adjudication of this issue; it further concluded that the false testimony was not material because of the substantial impeachment evidence against Ms. Cronin and because of other evidence apart from Ms. Cronin's testimony regarding Petitioner's guilt. Under the facts of this case and the applicable federal law, Petitioner has shown that the decision of the Supreme Court of Florida was contrary to, or involved an unreasonable application of, clearly established Federal law, as determined by the Supreme Court of the United States. Likewise, Petitioner has shown that the decision of the Supreme Court of Florida was based on an unreasonable determination of the facts in light of the evidence presented. For this reason, this issue is meritorious, and Petitioner is entitled to habeas relief on this claim.8

The Court denied relief on Guzman’s other claims and remanded the case for a new trial. The State appealed, and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit affirmed the district court’s decision, writing in part: “[A]fter carefully reviewing the transcripts from Guzman's trial and evidentiary hearing and the trial court's orders, we hold that the Florida Supreme Court's materiality determination was more than just incorrect—it was an objectively unreasonable application of clearly established Supreme Court precedent.”

Third Trial

In his third trial, Guzman was again convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to death. The penalty phase occurred on May 3, 2016 (just after the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Hurst).9 The jury recommended a sentence of death by a vote of 11-1.10

On direct appeal, in a decision dated February 22, 2018, the Florida Supreme Court affirmed Guzman’s conviction but remanded for a new penalty phase in light of Hurst.11

Resentencing

Following Florida’s new capital sentencing statute, Guzman, through his attorneys, unsuccessfully challenged the new statute and its application to his case.

Following the new penalty phase, on March 22, the jury unanimously recommended that Guzman be resentenced to death.

The jury also unanimously determined that the State proved all five aggravating factors beyond a reasonable doubt. The State Attorney’s Office issued a press release following the jury’s recommendation, which can be found here.

Under Florida’s 2023 capital sentencing statute, the trial court has the discretion to impose a sentence of LWOP rather than death despite the jury’s recommendation. Sentencing is not yet scheduled according to the docket.

Guzman v. State, 644 So. 2d 996 (Fla. 1994).

Guzman v. State, 721 So. 2d 1155, 1158 (Fla. 1998).

Guzman v. State, 868 So. 2d 498, 504-05 (Fla. 2003).

Id. at 511.

Guzman v. State, 941 So. 2d 1045 (Fla. 2006).

Id. at 1052 (Anstead, J., dissenting).

Guzman v. Secretary, Dep’t of Corrs., 698 F. Supp. 2d 1317, 1333-34 (M.D. Fla. 2010).

Id. at 1335.

Guzman v. State, 238 So. 3d 146, 152 (Fla. 2018).

Id.

Were the hair tests/identifications important in this case? If so, did the court consider the limits of these tests: before 2000, the science of hair analysis could not make an identity to one person and therefore are invalid evidence.